Racial discrimination: a forgotten facet of diversity & inclusion policies?

Following the publication of several studies demonstrating the existence of widespread racial discrimination, and under the impetus of public authorities, diversity and inclusion policies were at first implemented across French companies during the noughties. These measures were in response to strong evidence which showed that one’s “origin” (a word that refers to a hodgepodge of characteristics such as family name, parents’ place of birth, ethnicity…) as a trait for which people suffer from systemic discrimination (1). Hence the creation of the Diversity Charter in 2004, which focused on this criterion. Article 3 of the charter encourages signatory firms to commit to "being representative of the diversity of French society and its wealth of differences, including its cultural, ethnic and social components, across the workforce and at all levels of decision-making". (2)

However, more than twenty years on, measures relating to the prevention of and awareness raising regarding racial discrimination have largely disappeared from the D&I agendas of organisations. The subject is mostly dealt with at the local level, with companies setting up partnerships that include integration, mentoring or recruitment programmes for young people living in disadvantaged neighbourhoods, known as QPV as per their French acronym. (3)

Measures that are about making signatory firms welcoming to as many candidates and talents as possible. Yet, beyond this, very few firms analyse the day-to-day realities and internal practices based on ethnic or racial criteria.

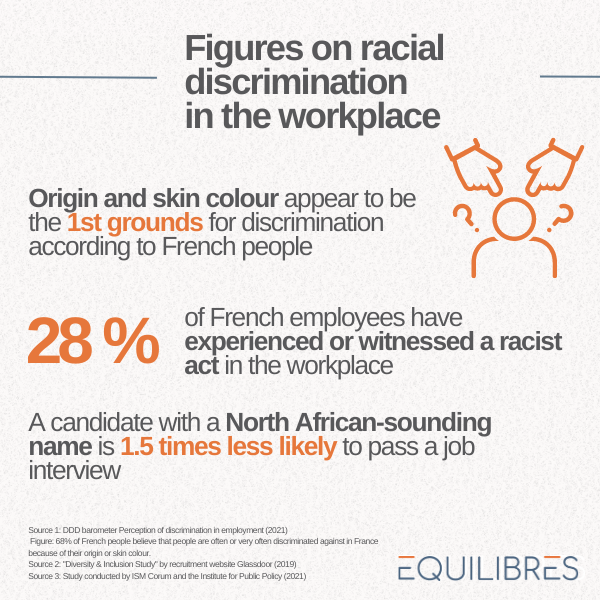

Frustratingly, numbers point to one tangible reality: despite the existence of the Diversity Charter, racial discrimination remains rife. According to a survey of the French population, one’s origin and skin colour appears to be the main grounds for discrimination (4), with 28% of French employees having been victims of or witness to racist behaviour or language in their workplace (5).

So, how does one explain the discrepancy between the extent to which companies claim to commit fighting racial discrimination and the lack of resources that are devoted to it?

A complex subject that is often neglected by firms

Several factors explain why the fight against racial discrimination is at a low ebb.

First, the fight against racial discrimination does not benefit from the same bevy of regulatory incentives as is the case for supporting the integration of people with disabilities, workplace gender equality and intergenerational equality. Of course, the criterion of origin is just one of the 26 criteria on the basis of which it is forbidden to treat one person differently from another, but there are no financial penalties for companies that do not actively commit themselves to the cause – such as by implementing an action plan aimed at eliminating or preventing discrimination on the basis of origin or promoting diversity within the company.

One reason for which ethnic and racial criteria are not associated with incentive-driven regulation is that it is difficult for French firms to identify employees by their “origin”. In fact, unlike the United States, where affirmative action based on ethnic or racial criteria can be applied in two areas - employment, the awarding of public contracts and until the landmark Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard ruling of June 2023, admission to universities - in France, the collection of statistical data based on such a criterion is strictly prohibited, even if its purpose is to identify discrimination and eliminate it (6). It is possible to analyse discrimination within organisations by using one’s surname as a proxy (this is how analysts determine whether a company has discriminatory hiring practices or not), but it does not systematically reflect ethnic or racial affiliation.

Furthermore, the fact that racial discrimination is given the least consideration in diversity and inclusion policies can partly be explained by the confusion that exists regarding how it is described and defined. Indeed, racial discrimination in the workplace is still too often associated with and compared to racism as an ideology (7), a way of thinking that is the preserve of a minority. However, racist behaviour and language - i.e. racial discrimination – do not necessarily reflect an individual’s belief in racist ideology. Discriminatory behaviour can be explicitly rooted in this, but not necessarily, and vice versa. For example, if a hiring officer chooses to exclude a candidate on the basis of their skin colour, this would be discriminatory, even if the request, say, for only having White employees, comes from a client or team manager. In this instance, the hiring officer would be committing racial discrimination without being themselves driven by racist ideology. Nevertheless, the hiring officer’s behaviour could be sanctioned at the disciplinary, civil and criminal levels, along with the original request to discriminate.

One must admit that the scope of racial discrimination is not always very intuitive. At what point does one cross the threshold of racial discrimination? What does it refer to?

Racial discrimination: what exactly does it refer to?

In law, discrimination is unfavourable treatment based on a legally defined criterion – of which there are 26 in French law today, both in the Labour Code and the Criminal Code (8) - in an domain that is also determined by law: access to housing, education, the provision of goods or services, or access to employment. Looking into racial discrimination in the workplace, it is access to employment that is of specific interest to us. Although hiring is undoubtedly one of the main situations where racial discrimination in access to employment takes place, discrimination can apply at any moment during one’s career, such as pay raises, job promotions, disciplinary sanctions, etc.).

The alleged perpetrator of discrimination may be a an individual or a legal person (an association, a company, etc.), a private entity, or a public one (a government service, a local authority, a public hospital or clinic), or several people at once.

As racial discrimination is an intersectional concept, there are several criteria prohibited by French law that are related to it:

Racial discrimination refers to all forms of unfavourable treatment (language, behaviour, procedures) on the basis of one’s “origin”, family name, physical appearance (e.g. skin colour), real or supposed membership of an ethnic group, nation, so-called “race”, or religious belief.

The adjective 'assumed' means that religious origin or affiliation is characterized based on an assumption, typically linked to a person's physical appearance, skin colour, surname or accent, without the person necessarily actually being of that origin, or of that faith.

Knowing the difference between 'being racist' and 'doing racist things' (9): a brave and necessary conversation

Racist behaviour can take the form of bullying, exclusion, and criticism unrelated to one’s work and based on real or perceived origin or religious affiliation. But it can also take the form of jokes or banter, inappropriate comments, rudeness... In short, what is now often referred to as a 'micro-aggression' in everyday language.

It is therefore necessary to draw a line between intentional or ideological racism and what is known as "ordinary racism" or "veiled racism" (11), which is not necessarily malicious in intent, but which is based on stereotypes and undermines the daily lives of employees who are victims of it.

In order to tackle racism and racial discrimination in the workplace, it is necessary to be able to identify its many forms. What lies behind the notion of racism? Why not adopt the logic of bias and stereotypes rather than that of isolated individuals in the company's prevention policy?

The concept of intentionality is central to the issue of racial discrimination, and of all forms of discrimination in general.

The definition of discriminatory harassment, which is a form of discrimination (or psychological harassment if it is recurrent), emphasises the possibility of racist language or behaviour being either guided by intent ("the purpose"), or not (in this case, we are interested in the "effect"). It is defined as follows:

"Any language or behaviour relating to [a criteria of discrimination], that a person is exposed to, and that has the purpose or effect of violating their dignity or creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment" (10)

This kind of language or behaviour - jokes about a person’s skin colour, origin or religion - are all microaggressions that are no less reprehensible in that they can "undermine the dignity of or create an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment" for the victim, all whilst impacting the latter’s health and self-esteem.

In this respect, humour is often used to legitimize racist behaviour. By accusing the person who is the butt of a 'joke' of not having a sense of humour, its perpetrator engages in behaviour that is exclusionary, thus socially sanctioning the receiver. The receiver is punished twice over: a first time, as a victim of racist language or behaviour, and a second time, by being excluded from the group that laughs at the joke.

To remove the moral burden from the issue of racial discrimination and to tackle it head-on, companies must deal with it from the perspective of ethnic and racial stereotypes, which are subconsciously ingrained in us all. It is therefore up to companies to ensure that their stakeholders find common ground on the issue of racism and racial discrimination by being as instructive as possible when it comes to explaining and understanding microaggressions as well as unconscious stereotypes, along with their impact both on individuals who are victim to it and their work group.

What benefits do companies which take up this issue stand to gain?

In addition to obvious ethical considerations, the benefits for companies that decide to tackle discrimination head-on are numerous.

First, the risk of litigation for discrimination or discriminatory harassment is naturally lower, as preventive measures have been implemented.

Second, stakes are also high in terms of image and corporate reputation, which are impossible to ignore. Indeed, companies are increasingly denounced on social networks or in the media when they are accused of discrimination. In France, the 2023 to 2026 national plan to combat racism, anti-Semitism and discrimination linked to origin also reaffirms the "implementation of a genuine policy of reinforced testing on discrimination in hiring" (12), with the government regularly organizing CV screening campaigns to identify which firms carry out discriminatory practices.

Last, several publications and studies have demonstrated the positive impact of having an ambitious diversity and inclusion policy on employee performance, well-being at work, spirit of innovation and creativity, retention of talent, etc.

With what levers can a company act?

To prevent racial discrimination and thus contribute to promoting diversity and inclusion, organisations can implement measures at several levels.

As mentioned above, it is up to companies to deal with racial discrimination as a subject that requires the utmost attention, in its intersectionality with other D&I topics, and by raising the issue of subconscious stereotypes.

- Measuring inequalities in treatment or their experience

Action plans should start with a diagnosis (both objective, based on data - and subjective, based on employees' feelings). In terms of racial discrimination, the French legislative framework allows for monitoring, via the personnel register, to ensure that there are no unexplained differences between employees on the basis of surname in hiring or during career development.

Furthermore, if the company has a formal reporting system for discrimination, it is worth noting the number of referrals concerning alleged discrimination on the basis of origin.

Finally, an increasing number of firms now include questions on diversity and inclusion in their annual quality of working life barometer. In this context, it is quite possible to include questions that enable respondent employees to disclose their origin, itself defined as referring to specific geographical areas (Africa, the Caribbean and the West Indies, Asia, North Africa, Europe, etc.) and countries (France, Algeria, Portugal, Senegal, Turkey, etc.), and then to cross-reference these questions with those relating to experiencing discrimination, either as a witness or a victim.

- Communication and training

Training managers and HR personnel in non-discriminatory hiring and career management is essential (and even compulsory, depending on company size) and has a strong impact on preventing inappropriate behaviour, as well as raising awareness, amongst all employees, of the issue of subconscious stereotypes.

You can communicate on the prevention of discrimination at regular intervals and at key dates (International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination; International Human Rights Day, etc.).

Last, you can support the creation of internal networks dedicated to this theme so that it remains grounded in reality.

- Agree on processes with stakeholders (customers, suppliers, etc.)

Racist comments and behaviour by customers or suppliers towards a firm’s employees are a regular occurrence.

To prevent any discriminatory requests or behaviour, you can, for example, write an ethical and good behaviour charter for your stakeholders to sign, and provide training for your employees to react should any form of discrimination arise.

Currently, firms’ diversity policies are primarily targeted at tackling the impact of disabilities, supporting gender equality and intergenerational cooperation - i.e. issues that benefit from political and financial incentives from the public authorities. It is now time to be more ambitious, by moving beyond a policy that focuses on the occasional resolution of individual cases of racial discrimination, and, as a company, by taking on the role of an accelerator of social progress. This includes proposing an ambitious policy of preventing and dealing with racism as a central component of its D&I strategy.

Emilie Fréchet

Consultant EQUILIBRES

SOURCES

- Systemic discrimination - Council of Europe definition: Systemic discrimination involves procedures, habits and a form of organisation within a structure that, often unintentionally, contribute to less favourable outcomes for minority groups than for the majority of the population, with regard to the organisation's policies, programmes, employment and services.

- Diversity Charter: https://www.charte-diversite.com/charte-de-la-diversite/

- Racism and racial discrimination at work - Anaïs Coulon | Dorothée Prud'homme | Patrick Simon

- DDD Barometer The perception of discrimination in employment (2021) - Figure: 68% of French people consider that people are often or very often discriminated against in France because of their origin or skin colour

- Study conducted by recruitment site Glassdoor 'Diversity & Inclusion Study' (2019)

- https://frenchamerican.org/wp-content/uploads/egalite-de-traitement-dans-lemploi-1.pdf

- Definition of racism as an ideology according to Wikipedia: Racism is an ideology which, based on the assumption of the existence of races within the human species, considers that certain categories of people are intrinsically superior to others

- Discrimination - French legal framework: Article L1132-1 of the Labour Code and Article 225-1 of the Criminal Code

- Racism and racial discrimination at work - Anaïs Coulon | Dorothée Prud'homme | Patrick Simon

- Article 1 of law n°2008-496 dated the 27th of May 2008

- Philippe Bataille, Racism at Work

- https://www.enseignementsup-recherche.gouv.fr/fr/plan-national-de-lutte-contre-le-racisme-l-antisemitisme-et-les-discriminations-liees-l-origine-2023-89325